Tom Hammick

Lunar Voyage

Overview

Drawing from a wide range of sources, from Japanese woodblock prints to Northern European Romantic painting, utopian Modernism and contemporary cinema, Hammick’s depictions of isolated human dwellings grounded in uncanny dream-like settings summon the uneasy atmosphere of a psychologically-charged thriller, or a dystopian suburban nightmare.

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives... on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.” - Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, 1994

British artist Tom Hammick has described landscape in his work as a metaphor to explore an “imaginary and mythological dreamscape.” Drawing from a wide range of sources, from Japanese woodblock prints to Northern European Romantic painting, utopian Modernism and contemporary cinema, Hammick’s depictions of isolated human dwellings grounded in uncanny dream-like settings summon the uneasy atmosphere of a psychologically-charged thriller, or a dystopian suburban nightmare.

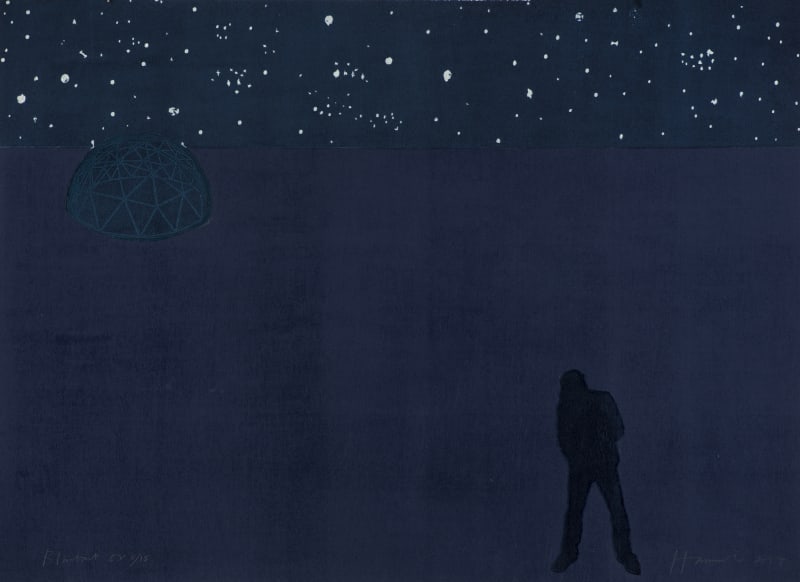

In the present exhibition of woodcuts Hammick conjures a metaphorical journey, in which his central character, an archetypal artist or poet, leaves the nurturing environment of life on earth to explore a paradoxical desire for freedom and isolation on another planet. A suite of seventeen woodcut prints traces the cyclical path of this lunar voyage, following his descent into chaos or an implied ‘lunacy’, before his return to the more concrete reality of his earthly home. This narrative cycle is complicated by repeated motifs, and the haunting presence of apparitions sparked by memories or dreams of those he has left behind.

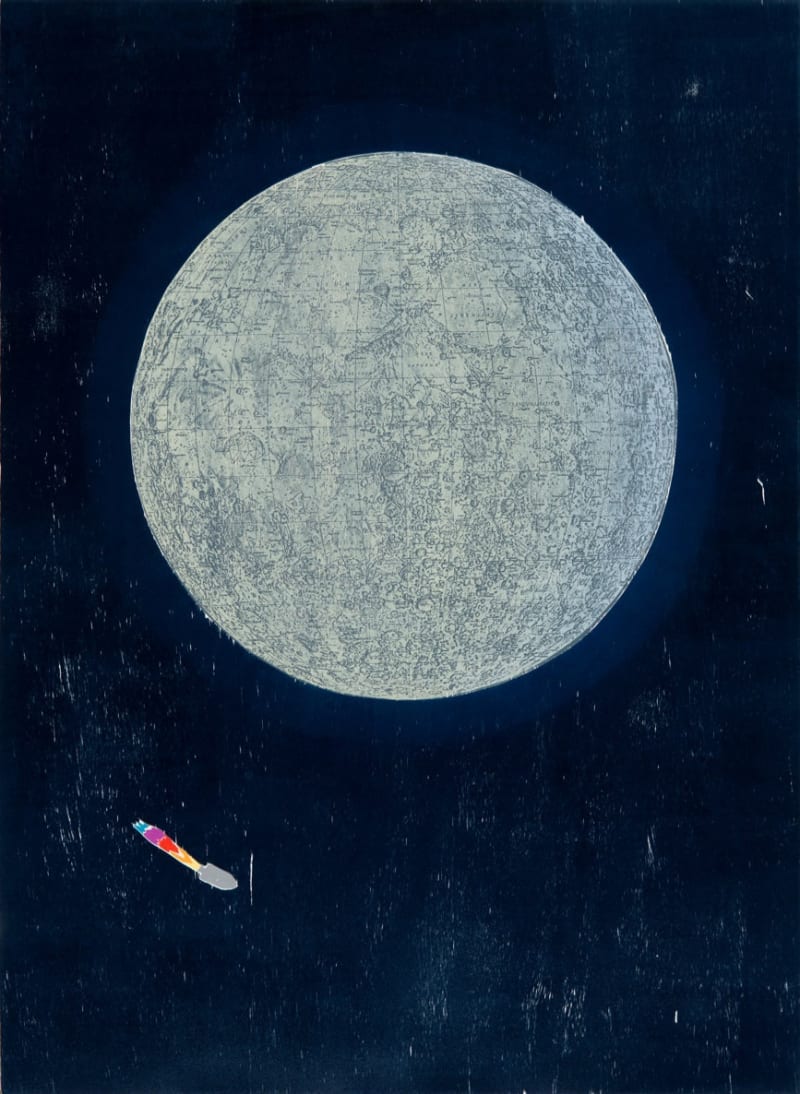

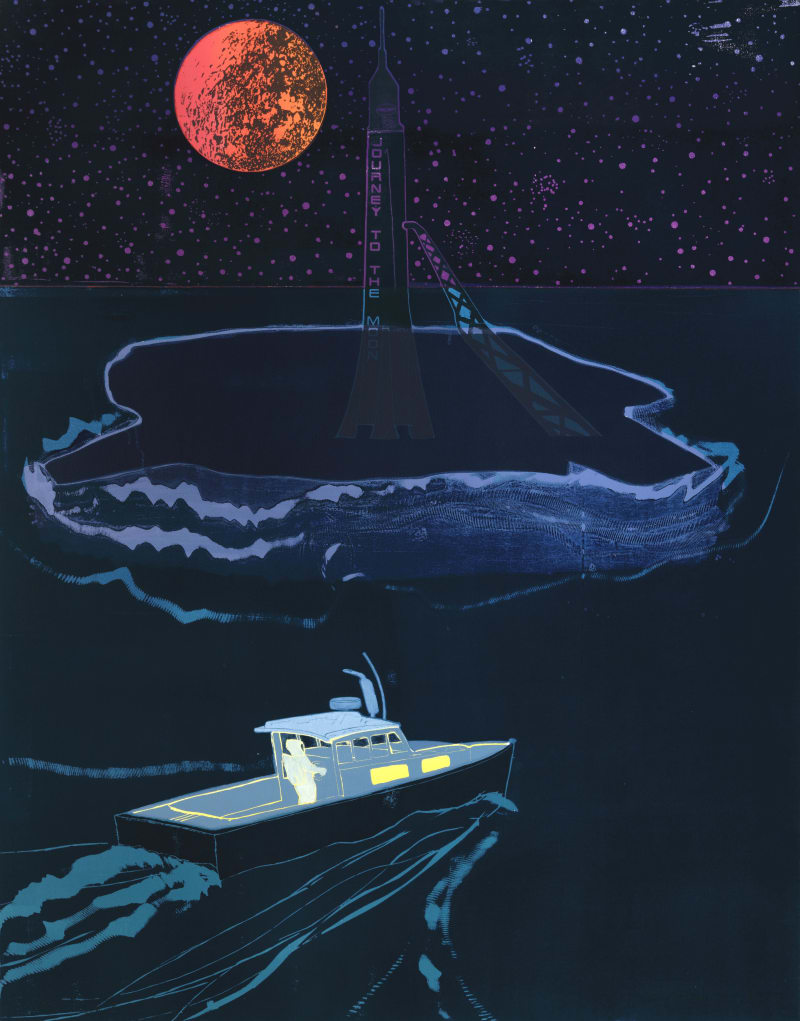

The cycle begins with Cloud Island, viewed as though flying high above the scene. The island is populated by a single house, in which a family can be seen going about their domestic activities, surrounded by a lush garden and a canopy of ornamental trees. The scene, symbolizing a prelapsarian Eden, is watched by the voyager from his boat, as he prepares to leave. This tranquility is ruptured in Journey to the Moon, where curling forms in golds, reds, pinks and turquoises swirl around the base of the composition, evoking the roar of rocket engines. In contrast, the infinite midnight blue of the solar sky in Star Path suggests complete silence, as the ship leaves the Earth’s atmosphere. In Sky Atlas, the space capsule continues its weightless journey through space, implying a new-found alienation and abandonment of the past, while the design of the capsule portrays nostalgic dreams of space travel found in comic books and outmoded computer graphics.

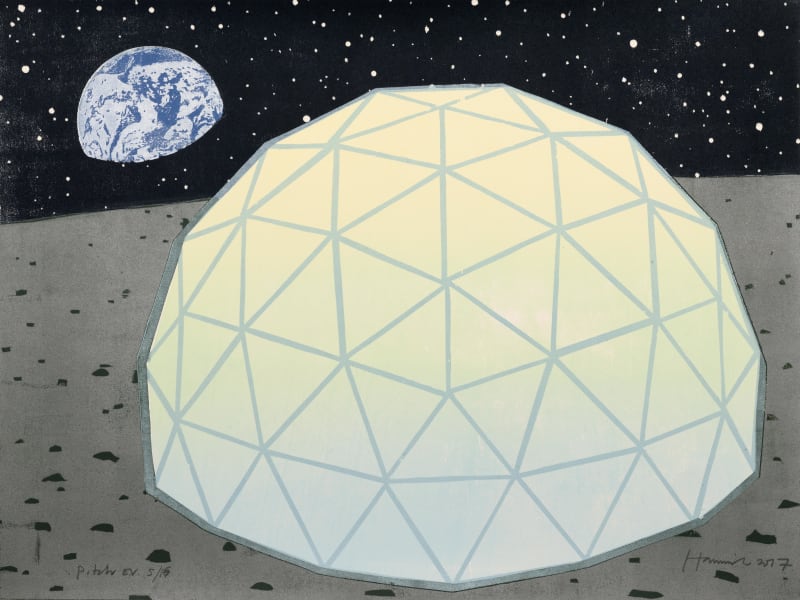

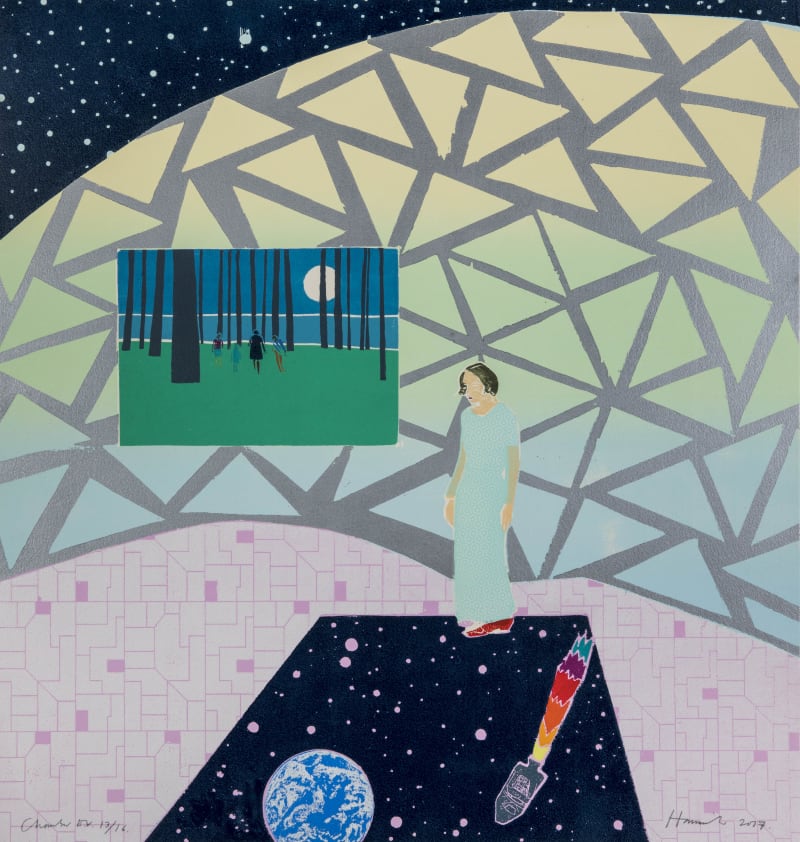

In Terrestrial, four standing figures, a woman and three children, gaze through the trees of the earthly island habitat up to the distant moon. The evocation of their isolation and loss is measured with a sense of mystery and longing, the figures appearing as though recalled in a dream, or dreamers themselves. As the cycle continues, the image Terrestrial recurs on the walls of the makeshift space station, suggesting a vision or memory summoned from earth. The space station (a spherical structure, reminiscent of the geodesic domes designed by R. Buckminster Fuller) is also occupied by the spectral presence of a mysterious female figure. Woven within this latter sequence of images are references to the feature films of Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tarkovsky, bringing to mind the striking sets of Kubrick’s The Shining and the romantic resurrection of psychologist Kris Kelvin’s wife Hari in Tarkovsky’s Solaris.

In Sleeper, the voyager appears to float weightlessly above the scene of his earthly home, recalling the drifting figures of Chagall’s Above the Town. Surrounding him, delirious visions of sequences of events on Earth prompt questions about the true nature of his journey, and whether he ever left home at all.

The antipodal shift between the Earth and the stars, and between geocentric and heliocentric viewpoints, reflects Hammick’s concern with the fragility of the environment, relating to notions of home and identity. He says: “The key Confucian motif in Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot is that actually there is no place for us to go. The physical escape in the series, leaving earth for the stars, is in fact a selfish and unrealistic act and could be seen as a fantasy. We must dream on Earth, and we need to be aware of our responsibility as custodians of this planet to conjure up ‘Heaven on Earth’.”

ABOUT TOM HAMMICK

Tom Hammick (b.1963) is a British painter and printmaker, based in East Sussex and London, UK. He was the winner of the V&A Prize at the International Print Biennale, Newcastle, UK in 2016, and the print Violetta and Alfredo’s Escape, 2016, was acquired by the V&A. Hammick has work in many major public and corporate collections including the British Museum (Collection of Prints and Drawings); V&A (Victoria and Albert Museum), UK; Bibliotheque Nationale de France (Collection of Prints and Drawings); Deutsche Bank; Yale Centre for British Art; and The Library of Congress, Washington DC.

Drawing from a wide range of sources, from Japanese woodblock prints to Northern European Romantic painting, utopian Modernism and contemporary cinema, Hammick’s depictions of isolated human dwellings grounded in uncanny dream-like settings summon the uneasy atmosphere of a psychologically-charged thriller, or a dystopian suburban nightmare.