Figurative artist Lucy Jones is renowned for her richly coloured works, exploring the internal in her intimately personal portraits and the external in her expressively raw depictions of the British landscape. This retrospective exhibition spans a period of over 30 years, from the beginning of Jones' career (shortly after graduating from Camberwell College of Arts, the Royal College of Art and the British School in Rome) to work created during the recent lockdown. The works on display trace Jones' developing style, bringing together the two elements of her practice and revealing how they inform and nurture each other: the portraits allow her to address a complex kaleidoscope of human emotion and philosophies of the 'self', whilst her landscapes offer a more neutral space. "People tend to like either the landscapes or the portraits, and people who like the one don't understand why I do the other, but for me the two go absolutely hand-in-hand" says Jones.

|

Lucy Jones

|

Lucy Jones speaks to actor Russell Tovey and gallerist Robert Diament for Talk Art, a podcast dedicated to the world of art featuring exclusive interviews with leading artists, curators & gallerists, and friends from other industries like acting, music and journalism.

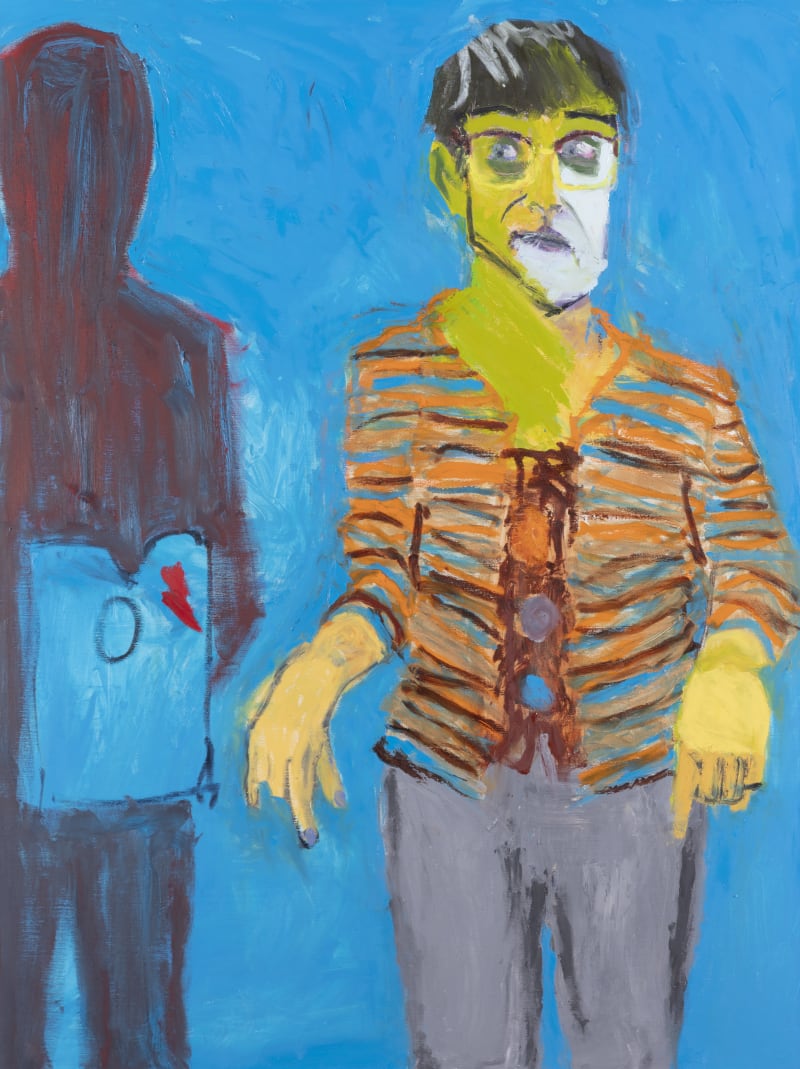

Lucy Jones’ distinctively provocative self-portraits address themes of ageing, femininity, self-image and disability. Jones, who was born with cerebral palsy, has faced the frustrations of her disability over-crowding people’s perceptions of her. Her self-portraits often challenge the way others see her: by using her defiant ferocity, vulnerability and wry sense of humour she turns the attention back onto the viewer. This is evident in works such as With a Handicap Like Yours..., in which an extra disembodied hand appears from the side of the canvas, “poking and prodding at institutional attitudes” and misplaced comments she has received. “The point is here that having three hands may truly be unusual and maybe the doctor is referring to the third hand!”. Just Looking, Just Checking on You depicts Jones' figure, arms curled around her knees, angled as if the viewer is looking at her from slightly above, with the works title painted directly onto the canvas in reverse. The aim is to recreate the experience of reading with dyslexia, the invisible source of a struggle Jones has had her entire life.

Initially, Jones found making self-portraits difficult: “I had not liked looking at myself in the mirror. I felt sexless. Things have changed quite a lot in the last few years and depression is far less prominent. I met my husband Peter just over thirty-one years ago, and my confidence grew. I began to paint the whole of me and paint the awkwardness of how I look – which is both personal and common to us all.” As a result of her consistent practice of self-portraiture over many years, she explains that her approach to self-portrayal has become "bolder, more commanding”, and her voice more unembarrassed as time has gone on.

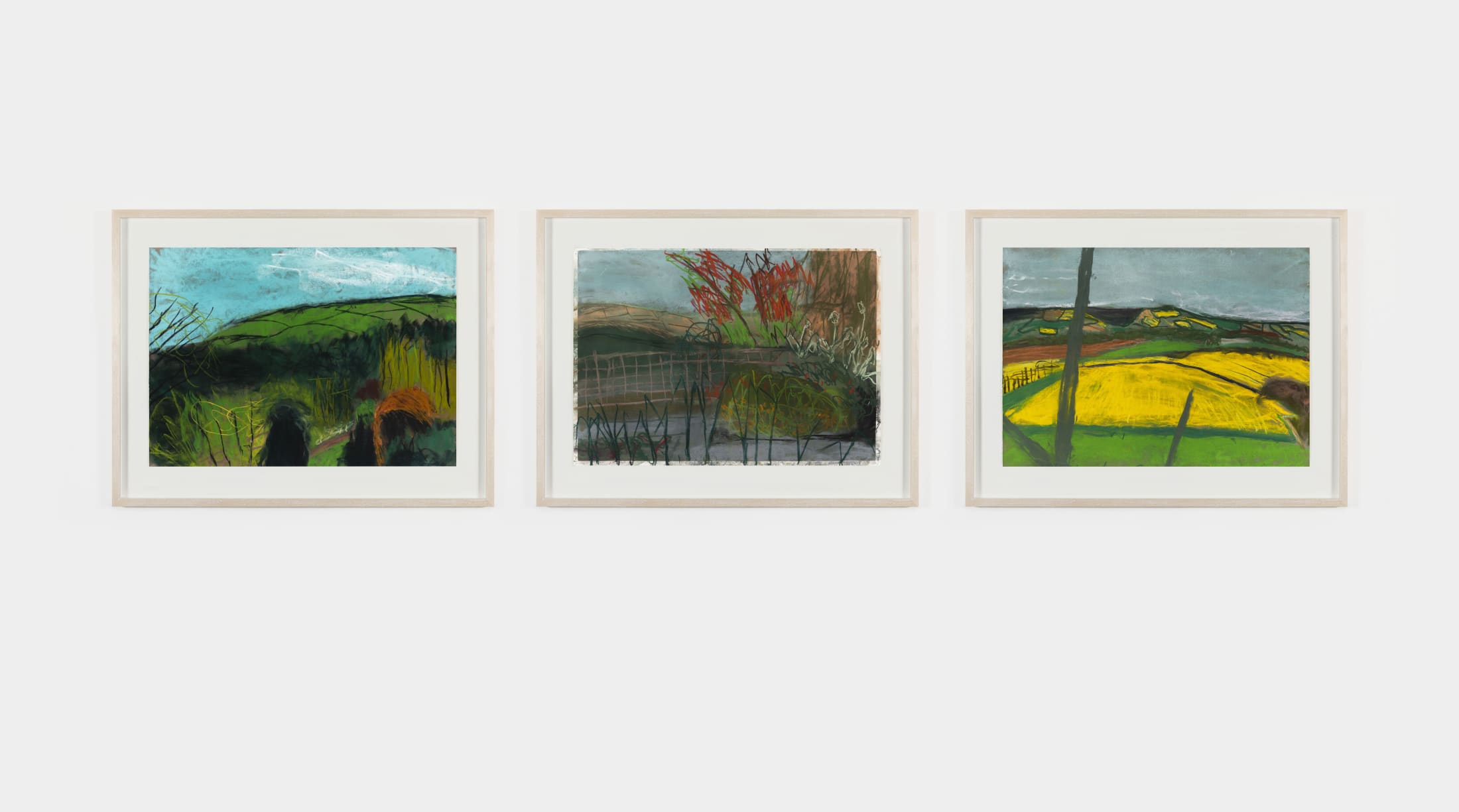

Jones believes that the “unseen struggles” behind making the work are as equally important as the overt messages laid bare in her portraits. Since her move to the Shropshire countryside in 2004, she has begun to venture into the landscape, placing a board on the ground and kneeling for several hours to create pastel or watercolour works, which usually become the basis for large landscape paintings years later. For Jones, these intensive and often paintfully uncomfortable sessions have brought emotional range and interiority to her landscape works, the landscape becoming irretrievably "Inscape". Critic Jackie Wullschlager wrote that Jones' more recent landscapes have developed a "newly defined sense of quiet vulnerability and vigorous determination that had always been present in the self-portraits".

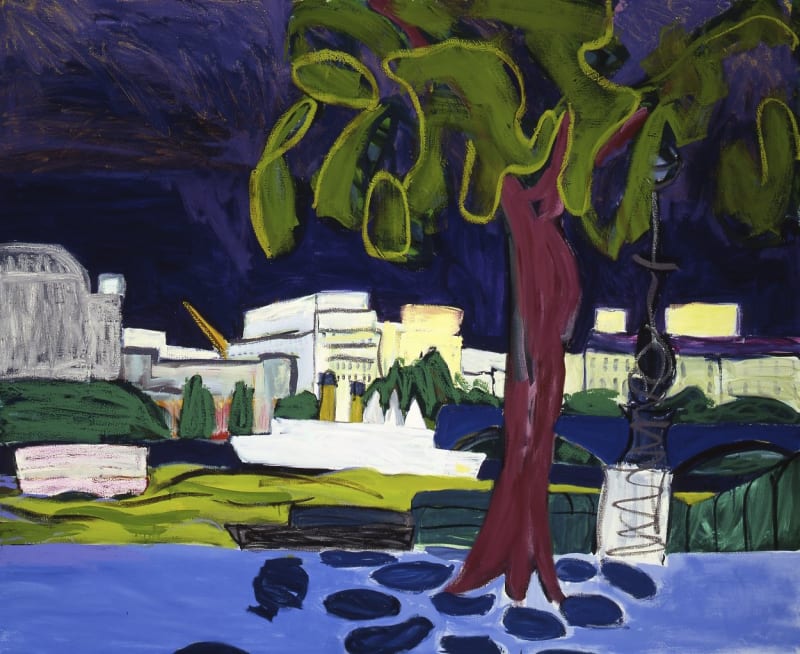

Just as the moods and atmospheres of her portraits can be alternatively celebratory or dark and foreboding, so too can her landscapes. This is evident in the degree of looseness or sharpness of stroke and varying colour palettes she employs, her choices being broadly subjective but equally evocative of the scenes climate and season. In comparison to the vivid strokes of Lead You Up the Garden Path, we see muted colour palettes and tight sharp marks in paintings such as Prelude 2020, created during the recent lockdown; in So Much Mud, October and Night to Come the tempestuous black-to-mauve clouds shroud the bright lilac and blue skies on the horizon. Writer and critic Philip Vann has compared paintings such as Night to Come to those of Maurice de Vlaminck (1876–1958), describing them as a "visionary interplay between ominous, nocturnal darks and the lights of illumined vistas, so that each picture affects the viewer with the kind of mystically transporting depth exerted when contemplating medieval stained glass or the stormy landscape and seascapes of surely the most expressionist-leaning of all the original Fauvist artists".

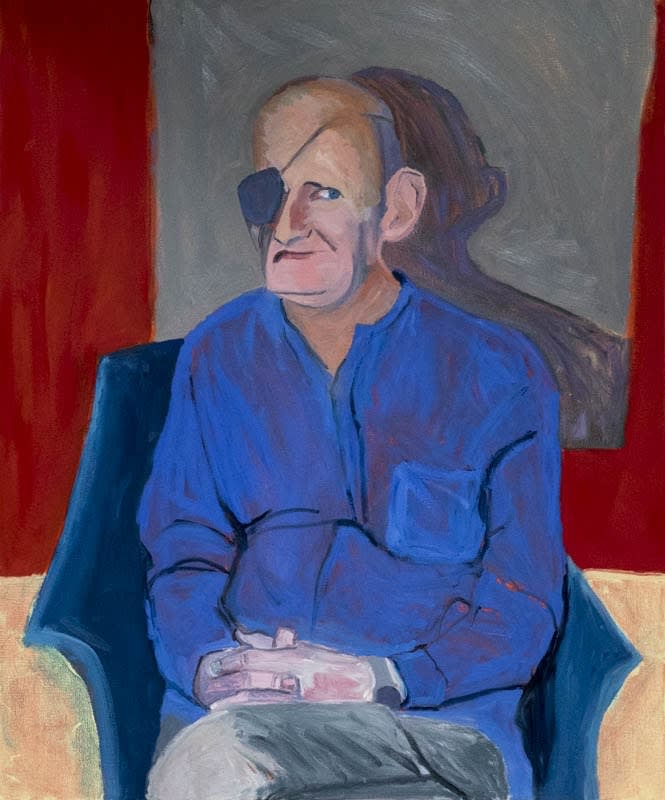

Since 2015, Jones has become more attracted to the challenges of painting those close to her, as well as taking on a portrait commission of the artist Grayson Perry in 2018, approaching them with the same unflinching honesty as with her self-portraits. While the rhythmical landscape paintings tend to be intricately detailed, the figures in Jones' portraits, which are almost life-sized, are framed by dense voids of layered colour, suggesting a physical and three dimensional backdrop.

Jones has known each sitter personally, enabling her to capture their unique mannerisms and energy with a powerful simplicity. In the portrait of Perry, Jones states “He’s very expressive; he is such an impatient live wire; he goes at such a pace. He keeps moving; he keeps talking; when does he actually rest? The hand raised towards his head is not quite touching, it’s got potential movement.” Of Roger Partridge, the late British sculptor and close friend, Jones notes his “keen intellect, wry humour, the slight curl of the lips with an ironic touch to the smile”. Finally, her portrait of her father, which was painted from a photograph taken just before his death, captures him in an authoritative paternal pose, fully engaging with her and gesturing as she attempts to gain his attention in order to take a picture in profile, “But he said, ‘No, Lucy, the camera is there!’”.

Jones explains that her relationship with colour began after her time studying in Italy: “it was not until after Rome that I could look back on the light of Italy, the architecture and the many paintings and sculptures that I saw. This was when I started to use colour, to free it from its controlled areas, to let the marks in my work have a life. It was seeing things like Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel Ceiling, which was being cleaned – I was able to see it so close, almost to touch it, on the top of the scaffolding – big broad brush-strokes and wonderful complementary colours. Trips to New York to see all those collections of European and American art have influenced my paintings. Seeing how artists like Pollock, Gorky and De Kooning let the paint marks and colour live, and showed the joy of colour.”

During her time living in London in the late 1980s, Jones painted incandescent riverscapes of “the simple architectural spaces” around the South and North Bank of the Thames, depicting scarlet church spires, purple pathways and crimson bridges across each side of the city. These scenes are dream-like, though heavily rooted in her precise observations of the scene. In a conversation with the curator and art writer Judith Collins in 2006, Jones explained that the “main difference between the self-portraits and the cityscapes is that I am not looking directly at myself. With the cityscapes, I am looking out on the world that is common to everyone, but my experience of that world is of course different – chaotic and difficult. It is this difference that is reflected in the cityscape paintings – and, like the self-portraits, these have changed as I have changed. London bridges have been a big part of the cityscapes. We can see in this the joining of two parts of separated land – like the two halves of myself in the portraits.”

Lucy Jones: Works on Paper

To coincide with this online exhibition click the banner below to see a curated selection of Lucy Jones' works on paper, available to purchase online.