Revisiting The Decameron

Overview

During the first days of the lockdown, I found myself remembering the introduction to Boccaccio’s Decameron with its description of the 1348 plague that killed 100,000 people in Florence. The echoes of our own experience were uncanny: how “one citizen avoided another”, people “died without a single witness” and few were “the bodies accompanied to church by more than ten or twelve neighbours”. The setting for this collection of a hundred stories, which Boccaccio imagined being told on a secluded estate outside Florence by a group of self-isolating young people, suggested another parallel: they were the Renaissance equivalent of Netflix.

Designed to relieve melancholy, The Decameron is essentially escapist. Over the centuries its stories have inspired artists from Botticelli to Holman Hunt, and I was curious to see whether their pungent mix of morality, brutality and bawdiness, with its invitation to subversive reverie, would resonate with contemporary artists under lockdown. When I floated the idea of a Decameron-themed show to various artist friends, the response was immediate and enthusiastic. This exhibition is the result.

Each artist has brought their own perspective to the stories. Jiro Osuga relishes their bawdy humour and gives it a contemporary spin, while Tim Shaw finds echoes of fertility rituals designed to keep us from harm. Lisa Wright focuses on the stories’ connection with nature, Shani Rhys James and Susan Wilson on the way they play on our deepest fears. Mick Rooney and Freya Payne reflect on isolation, Marcelle Hanselaar on personal loss, Stephen Chambers and Ken Currie on sickness and death, Tom Hammick on love and Amanda Faulkner on hope. Tai-Shan Schierenberg highlights the tension between Christian morality and freedom, while Nicola Hicks celebrates the sheer thrill of storytelling. In different ways they have all brought the stories alive, casting new light on our experience of this pandemic and reminding us that, in the span of human history, it is far from unique.

When I first had the idea for this exhibition, I couldn’t find my copy of The Decameron and I went to my local branch of Waterstone’s. The assistant had never heard of Boccaccio and looked at me blankly. I tried explaining that he was an Italian Renaissance author who wrote the first collection of short stories in European literature. She looked unimpressed. “Could you spell that?” She checked on her computer and told me the book was out of print.

Boccaccio would not be surprised at this neglect. “I confess that there is no stability in the things of this world and that everything changes,” he writes in his Conclusion. But he might be gratified to learn that, in the midst of instability, his stories can still inspire artists seven centuries on.

Laura Gascoigne, Curator

"For an artist who sees himself as a sower of narrative seeds and one who is interested in both the beauty and the beast, The Decameron is a ‘gimme’.

“Love not only leads lovers to run deadly risks, but… persuades them to enter the home of the dead, pretending to be dead” - Filomena, The Ninth Day

Anyone who has brushed the cheek of Chaucer will have had, at the very least, the ghost of an encounter with these stories. The harvesting of tales into a collection delivered by a variety of voices, presenting a depiction of raw times, is consistent in both. The Decameron fuses tragedy with tenderness, lewdness with levity. It is an illustrative account of years of pestilence, whilst also providing a mirror reflecting the personal voices of the narrators.

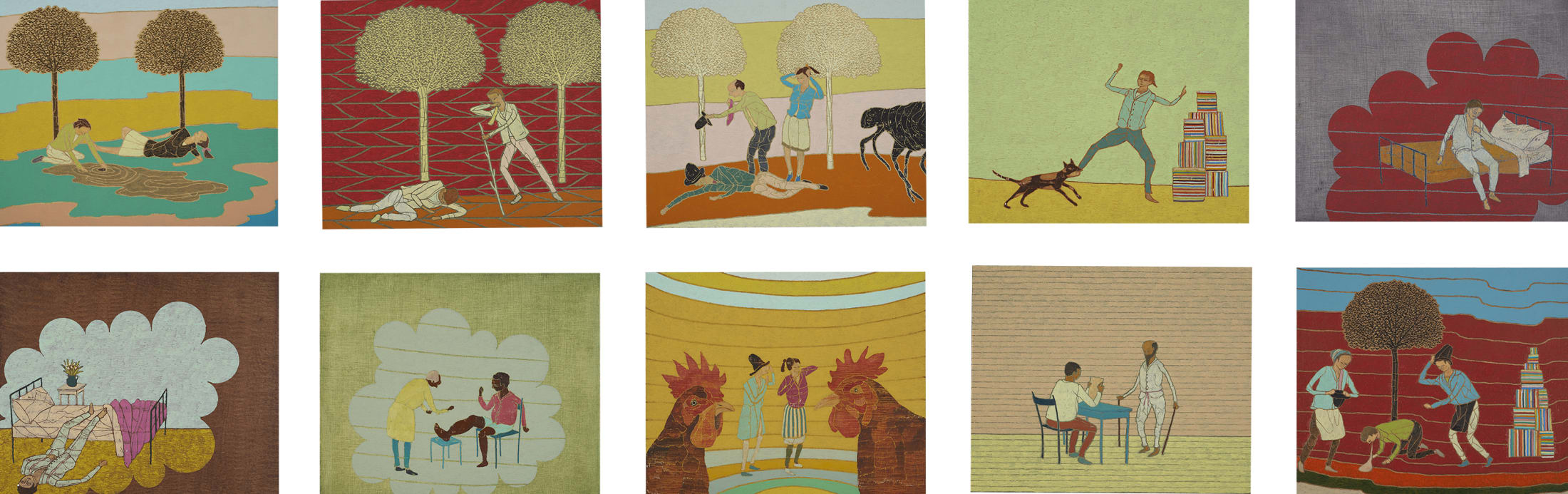

This group of ten paintings (the number ten lies at the heart for the book; ten narrators each telling ten stories) was made before these Covid days. I have, over many years, reflected on the relative lack of depictions of ‘sickness’ in contemporary art. Not absolute, of course, and the reasons are understandable since art has largely shed its role as catharsis, but… it is a strong seam for imagery and discusses what we all know: that when we are ill we think on death.

These paintings were made in Berlin following weeks travelling through Latin America. In areas of high illiteracy pharmacists describe their treatments using pictograms, innocent paintings showing, in several instances, potentially catastrophic diseases. I like their charm, their reassurance, their invitation to come inside. Each of the paintings in 50 Ways to Knock You Down refers to an ailment. I wished them to be both dark and light." - Stephen Chambers

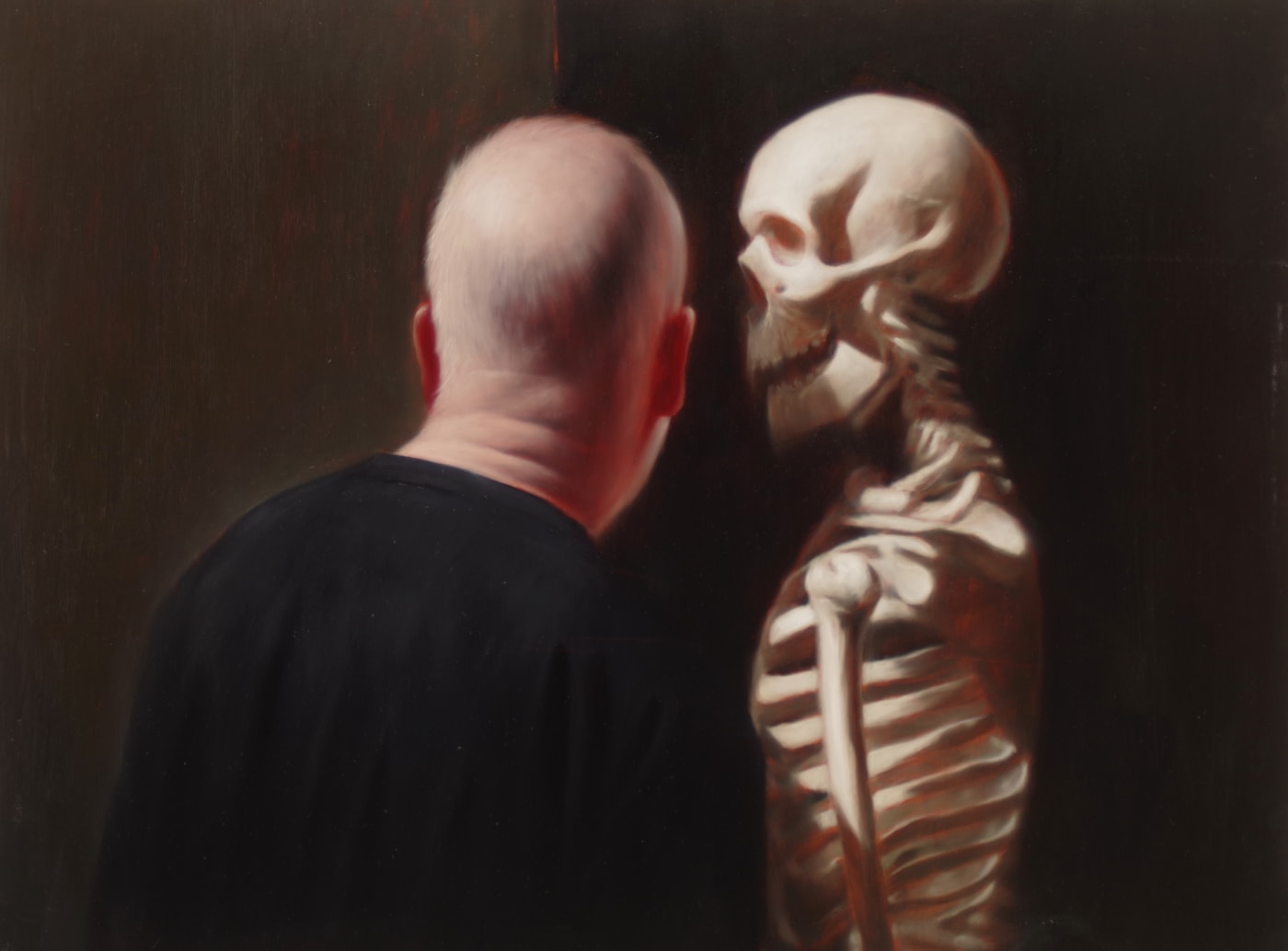

KEN CURRIE

Skeleton Whispering, 2019-2020

Oil on panel

46 x 61 cm | 18 1/8 x 24 1/8 in

"The pandemic seems to have temporarily punctured the complacent triumphalism of our civilisation and reminded us of the vulnerability and contingency of human existence. As has been pointed out there are more viruses on Earth than stars in the universe. No serious artist would ever claim the gift of prophecy but looking at this painting from 2019 again it does seem strangely prescient in our current emergency." - Ken Currie

Oil on canvas

Enquire

Oil on canvas

"In Boccaccio’s tales there seems to be a constant tension between the Church or societal norms based on a Christian moral framework and individual freedom. I hope my painting is able to convey that tension with the boat symbolic of adventure and escape (or possibly the futility of that dream)." - Tai Shan Schierenberg

SHANI RHYS JAMES

Nastagio I, 2020

Oil on gesso board

50 x 75 cm | 19 3/4 x 29 1/2 in

SHANI RHYS JAMES

Isabella, 2020

Oil on linen

122 x 152.5 cm | 48 1/8 x 60 1/8 in

SHANI RHYS JAMES

Nastagio II, 2020

Oil on gesso panel

50 x 75 cm | 19 3/4 x 29 1/2 in

"It is interesting how people today are psychologically coping with this pandemic. Either they are in complete denial - doing yoga, planting vegetables, knitting and creating, not looking at the news, not wanting to engage at all with the situation - or they are obsessed with watching the news, stressing and putting all the articles about the scurrilous government on FB.

In The Decameron the young people are doing the former, escaping to beautiful retreats away from the plague raging in Florence, telling each other tales which are seemingly innocuous. Yet they mask violence, misogyny and hedonistic pleasure. Adultery seems the order of the day!

In the story of Isabella and the Pot of Basil, the fifth story told on the fourth day, Isabella takes her dead lover Lorenzo’s head and hides it in a pot where she plants sweet basil. Her brothers have killed Lorenzo and buried him, but after he appears to her in a dream and tells her where he is buried she digs up his body and cuts off his head to keep as a memento. I decided to put the head on a platter before being placed in the pot. The violent act of decapitating the lover’s head was glossed over but I saw it as an image similar to John the Baptist’s head on a platter.

In the story of Nastagio degli Onesti, the eighth story told on the fifth day, a young man of noble family falls in love with the daughter of another noble family who does not requite his love, and he loses his fortune in his grief. Whilst wandering in a wood he sees a woman pursued by dogs and a man on horseback; she is killed and her heart and intestines ripped out and fed to the dogs. In life the woman refused to return another’s love and her punishment in the afterlife was to be repeatedly hunted and killed. Botticelli illustrated the story in tempera on gesso on four wooden panels, now in the Prado, forming part of a wedding chest intended as a warning to women: do as your husband bids or you will be punished.

My first painting of this subject in oil on gesso on two panels is quite light-hearted. It is as if the storyteller is inspired by seeing the motif on the wallpaper or the pot and it sparks her imagination. The second painting I have placed in a contemporary setting, an urban wasteland where a man has set his dogs on a woman stripped of her clothes. It is a woman’s worst fear." - Shani Rhys James

SUSAN WILSON

The Flight and Chase Through the Woods - Third Story on the Fifth Day, 2020

Oil on linen

102 x 127 cm | 40 x 50 in

"I watched the pandemic from the very first. I was curious about it. I had been trapped in the Los Angeles International Airport transit room waiting to have my passport read for three hours in December, inches from other passengers snaking tightly around the hall, some wearing masks. Flights had come in from everywhere and I was fearful of catching colds, flu, anything going… From this moment I began to be afraid in London. I knew how many flights come in and out of here, and before going to Camberwell School of Art I had nursed for seven weeks at The London Hospital For Tropical Diseases. A consultant used to talk to us about ‘The Next Pandemic’ and how airports would of course be the points of arrival for viruses.

From my return I avoided packed tubes, wore a mask if they were rammed, took circuitous routes across London, always watching for sniffles. At night all through winter I walked with my dog at dusk and made rough drawings in a tiny sketchbook.

I’ve been thinking for years about colour in the dark, how figures emerge and vanish, how dogs zoom in and out. Boccaccio’s story of lovers being hunted through a wood in the dark is permeated with chaos, fear and suspicion; it connects back to a Renaissance painting I have always loved, Uccello’s The Hunt in the Forest in the Ashmolean Museum. Am I afraid of the woods in the dark? I do always strain my eyes to detect figures coming my way. I try to ‘read them’. People do run alarmingly as if in chase, and the dogs pick up on the chase and get excited. Dogs know exactly how to find people; that’s the scary bit. The Decameron’s Pietro stripped by thieves and nearly tied to an oak, that’s what we fear. Some malevolent happenings in the dark with the light of the city, the castle, beyond. Even the woodcutter cannot guarantee safety; that part of the story is brilliant. We all wanted safety and assurance before the pandemic struck. Now, it can’t be had. Really, it never could." - Susan Wilson

"Artists spend a lot of time alone cut off whilst outside the universe throws its toys out of the pram. A narrative painter like me waits for an image to arrive, whatever the subject is, and the viewer enters at a certain moment - if they give a damn - to wonder whether the image story has a beginning and an end.

The storytellers in The Decameron start, tell and stop.

These two images were made in full knowledge of the prevailing conditions of isolation and left me free to let them tumble unconsciously out. Little Inhabited Rocks, almost medieval in intent, shows simply our own little planets spinning off to God knows where. As for The Daughters of Sisyphus, he must have begat daughters and passed his burden on to them. The world has not changed.

Just leave food and drink on the doorstep forever. No need to step outside ever again!" - Mick Rooney

TOM HAMMICK

Love Divided: Adalieta and Torello, 2020

Oil on canvas

81 x 122 cm | 32 x 48 in

"The touching story of Adalieta and Torello is told near the end of The Decameron, the ninth story on the tenth day. It seems to me unusual in the book, as an example of conjugal love that is never compromised.

I have depicted the couple as chic contemporary Italians looking out across the sea to each other, Adalieta longing for Torello’s return from the Last Crusade. Before departing for war Torello had embraced his beautiful wife and generously told her that, if he did not return within a year and a day, she was free to marry whomsoever she wanted. In the story Saladin, the Sultan of Babylon, having been courteously entertained by Torello at his home in Istria when travelling incognito through Europe before the Crusade, repays his kindness by sending him home from Alexandria overnight with a time-travel potion concocted by one of his magicians. Torello has to get back lickety-split because the deadline is upon them and Adalieta’s family have bullied her into remarrying. He makes it home, she recognises him at the pre-wedding dinner and literally flings herself upon him across the table they are sitting at.

I was influenced by Piero della Francesca’s powerful diptych portrait of Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza. I based my painting of Adalieta on memories of a modern-day Sforza who lived in West London and I was keen on many moons ago. My impecunious state as a young painter didn’t help the longevity of the relationship, which was over as fast as it started!" - Tom Hammick

TOM HAMMICK

Returning from the Wars, 2020

Oil on canvas

140 x 200 cm | 55 x 78.5 in

SOLD

"In this second painting I have depicted the couple in a walled garden. Torello has literally dropped from the sky after his magic carpet ride home overnight. Adalieta, dejected and longing for her husband’s return, fails to recognise him in his Arabian garb.

I was influenced here by Quattrocento predella panels full of rich background detail, as well as by the carpets of flowers found in the tapestries of the time. I also wanted to try and play with depicting time unfolding across the painting as it does in the narrative. All the stories in the book have this compartmentalised movement, with the storytellers acting as intercessors between the characters in the narrative and their listeners in lockdown. As viewers of paintings we find ourselves in the same sort of back and forth dialogue. We know this story is going to end well but the painting stops short, just before the tension is released.

A final note on the crusader. Two years ago in New York, I visited Malcolm Morley’s show Tally-ho with Cecily Brown. The exhibition was mind-blowingly good and showed how it's OK for paint to have a physical, plastic presence even in figurative paintings with narrative. So by lifting this careering knight on his charger from Tally-ho I wanted to say thank you to Malcolm, and to Cecily for dragging me to his exhibition." - Tom Hammick

"What struck me reading The Decameron for this project was its sheer boisterousness and irreverence. In the book, husbands and wives cheat on each other as a matter of course, and the clergy of the day are ridiculed throughout for their rank hypocrisy. Even though the framing story is set during a dreadful cataclysm in which half the population of Europe perished in the most gruesome way, solemnity is in short supply in most of the stories. They are very far from introspective, despite being set during a quarantine: they take place not just in the city states of Italy but across the then known world, from Cathay and the Barbary Coast to as far north as the British Isles. But this is not so surprising after all. There is only so much sober reflection on the grimness of reality you can stomach at a time of crisis. Perhaps what we need at such times is not morbid self-flagellation, pious platitudes or sugar-coated sentimentalism, but the uninhibited exercise of the imagination.

I took my cue from this insight and spent three weeks during lockdown making a string of paintings loosely inspired by Boccaccio without worrying too much about what the paintings signified, and thoroughly enjoyed myself in the process. A Story from the Decameron I, II and III are just three of the dozen paintings that I made.

The oversized head with figures and architecture on top is a trope I have been using for a while. It could be read as representing the thoughts of the giant bearing the little scene on his scalp, which is appropriate for The Decameron as its stories are told by ten different narrators. The disparity in scale adds visual interest and extends the imaginary space beyond the edge of the canvas. For the style of architecture and the dress of the characters, I opted for a contemporary look rather than cod-medievalism. I am rather pleased with the wheelie bins teetering just above the giant’s ear in the first painting – they are probably the first wheelie bins that I have ever painted." - Jiro Osuga

TIM SHAW

The Mummers' Tongue Went Whoring Amongst the People, 2020

Wax and straw, to be cast and editioned in bronze or resin

26 x 32 cm | 10 x 12.5 in

"The series of six small wax and straw maquettes of mummers is very much shaped by meetings I had with the mummers on St Stephen’s Day in Northern Ireland. It has its roots way back in the early 1990s when I first saw an image of these masked straw men and women on the front of The Times. I thought wow, that is something that must have come from Africa and then I read the small print and realised these were the mummers just down the road from where I grew up, the Armagh Rhymers. I thought, how come I didn’t know about this growing up in Belfast? I guess in those days, during the Troubles, people didn’t travel around much; the city was very much the city and the countryside the countryside. It was very interesting to come across those images, which always stayed in my head.

It wasn’t until about 2008 that I actually met the Armagh Mummers; I went to visit them and they showed me their costumes and masks. Ask a mummer what mumming is about and good luck with getting a clear answer. When I did get an answer from one man he said: “I think it’s about making sure that things will be OK.” That could even be the title of this piece. The mummers’ maquettes are about the future, fertility, things being OK; I guess things that are universal and age-old, which still apply to where we are today. The idea is one day to create a group of these, possibly out of wood and other materials, a life-size installation for outside.

The film is of the building and burning of a 25ft Wicker Man at this year’s Summer Solstice. In Boccaccio’s Decameron seven young women and three men flee the city for the countryside to escape the plague (the Black Death), and tell stories to distract themselves from the horror. Nearly seven centuries on, a group of 20 people move from the town and the city to the countryside (Higher Spargo Farm, where the burning took place) to escape and self-isolate from the plague (Covid 19). On the Solstice a sacrificial offering of a Wicker Man with a Covid-19 head is made to the pagan nature gods of the West Country. One of the celebrants sings as the effigy burns." - Tim Shaw

NICOLA HICKS

She tied a string to her toe, 2020

Drawing charcoal on paper: 216 x 243 cm | 85 x 95.5 in

Plaster: 15 x 36 x 35 cm | 6 x 14 x 13.5

I also found the party and their cultish rota a bit of a turn off, quite irritating, in fact really irritating! And then I had it: my response to The Decameron was to imagine the Telling. The power of the teller, the Ghast of the spellbound, and the creeping shadows of human interaction." - Nicola Hicks

FREYA PAYNE

“While I weave these stories”/ isolation and transgression 1’, 2020

Oil painting on hinged wood, bone, acrylic and laser-cut text

35 x 23.5 x 4 cm | 13 3/4 x 9 1/4 x 1 5/8 in

FREYA PAYNE

"While I weave these stories”/isolation and transgression 2’, 2020

Oil painting on hinged wood, bone, acrylic and laser-cut text

35 x 23.5 x 4 cm | 13 3/4 x 9 1/4 x 1 5/8 in

"My title quote “while I weave these stories” comes from Boccaccio’s prelude to the fourth day, as he defends the appropriateness of his writing project. Despite the multitude of archetypal stories represented in The Decameron, in the end it was something very generic about our human relationship to narrative that connected with me as a starting point for this project. The impulse to contain and shape our experience through storytelling is as fundamental today as it was in 14th century Italy. I suspect in times of insecurity and fear the need for storytelling is even more acute, as we require more confirmation that we have form and shape, a past and a future. We like to fit ourselves within a comprehensible frame of reference, and distance ourselves from the sense of things being either empty or out of our control.

We narrate our lives in many ways of course. I do not use the proliferation of digital platforms, so my focus with this artwork is the private experience of recollection. I am interested in the mind’s work of memory and projection. This comes from my own intense visual ‘day-dreaming’ during lock-down and from watching others, lost at their windows, gazing out from their ‘isolation’, and immersed in their own thoughts. As I walk past houses and notice these faces, I wonder what they see. They remind me of desert mystics deep in their visionary world. Where are they? In the present, past or the future? What are the stories they are telling themselves to give shape to their day?

Boccaccio’s ensemble of young Florentines narrate tales that spin with the moral codes of their day, siphoning from the rich drama of human emotion. From their quarantine come stories of transgression and excess. In a situation of less, in our deserts of boundaries and restrictions, do we ‘invent’ more? In our minds wandering, do we allow more freedom to connect to archetypal themes, do we distil the powerful core experiences of love and loss?

My two works contain the portrait of a woman looking out from her ‘within’. The text opens the scene of reflection, digression, and transgression of the daydreamer. The format is of the 14C, a small wooden personal secular altar. Where the daydream or story goes is the remit of the viewer of the altar." - Freya Payne

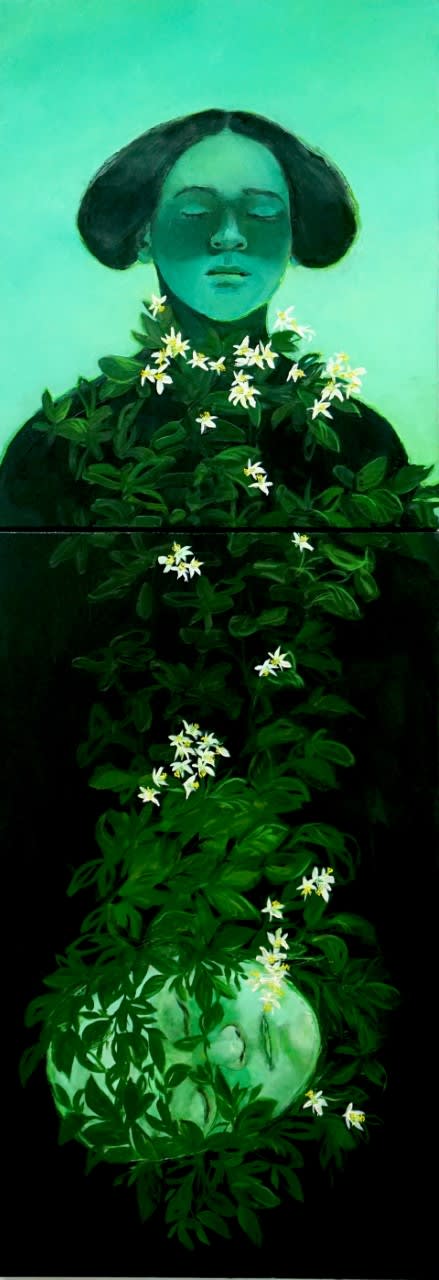

LISA WRIGHT

The Mystery of Tears, From the Fourth Day - Fifth Story, 2020

Oil on two joined canvases

140 x 50 cm | 55 x 19.5 in

"This particular tale, the fifth story told on the fourth day, seemed to resonate with some of the underlying themes in my work: the emotional territory of the transition from childhood to adulthood and our universal connection with nature.

I was captivated by the idea of Isabella planting basil in a pot to cover the decapitated head of her lover Lorenzo and watering it only with her own tears and the essence of orange blossom.

In this tale of youthful love, death and nature are forever entangled." - Lisa Wright

Chalk pastel on paper

Enquire

"Solitary or cooped up too closely, telling stories to oneself or to others. Imagining illness and death, or re-emergence into a healthier space, more verdant and with more cooperation between us and all other species and the natural world. Hoping." - Amanda Faulkner